‘Christ, he wouldn’t encourage you to come back, would he?', she muttered as they clambered through the crowds rushing out the doors of St. Ultan’s. A large, pre-emancipation era building originally constructed in a cruciform shape, the church was re-ordered and clumsily squared after Vatican II. The removal of reredos and railings remained controversial amongst many parishioners.

‘Keep the head down and nobody will see us’. Why should she chat with Dervla Farrell when their children weren’t in school anymore? Why listen to Linda Clarke’s incredulous screeching, ‘Is that really you?? My GAWD, I haven’t seen YOU here in ages!!’, when their children weren’t even children anymore? She didn’t know why she was there. It’s Christmas, she thought, you had to do something. Sure, it’s only once a year.

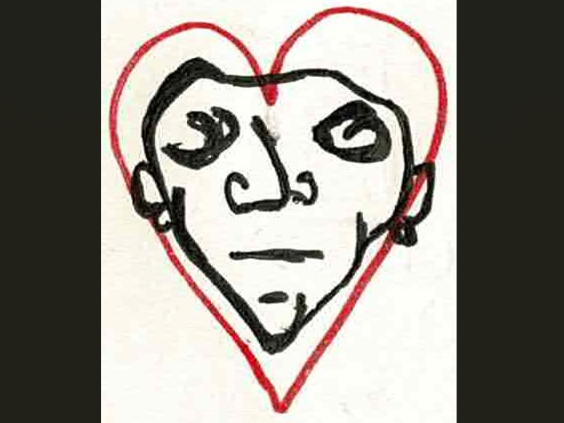

She thought of her parents, their complete and pious devotion. Christmas wasn’t Christmas without a midnight mass. Sunday wasn’t Sunday and Wednesday wasn’t Wednesday. The dim light of a sacred heart stretched far across her childhood. It didn’t mean much to her now, but you have to have something. She was glad they were dead before it kicked off.

Every day for the past few months the Report was discussed on the radio. Even the shock-jocks covered it. ‘Guess this sound! That’s right, it’s the arse falling out of Catholic Ireland!’ None of her children went to mass anymore, and she couldn’t blame them. Only baptised to get into school, Communions and Confirmations were just for the craic. It’d be harder for her to let it all go. But it takes time, she thought, it takes time.

They drove quick out the car park, careening around crowds gathered in circles discussing the Christmas. An awkward priest stood holding mince pies and cold sausage rolls. Not even the Eucharistic Ministers had a kind word to say as comparisons with the recently relocated Father Kearney spread around the yard. ‘He hasn’t half the pizazz as old Baz’, ‘I’m sure I saw him wince at the wine’, ‘Pathetic, that’s right, Pathetic’.

The New Year began and the radio switched back to old news. The M3 was almost complete, despite a decade of protest from environmentalists, academics, and artists. ‘Gobshites and hippies’, as one councillor put it. The motorway, which would cut straight through Tara, would slice her husband’s commute in half. It’d be nicer, too, getting into town a bit faster, but she’d never admit that in public. She sympathised with the protestors, even though she couldn’t connect with the more paganistic arguments delivered by tree-huggers and greasy-haired fans of The Hothouse Flowers and Clannad.

‘The motorway which will link the towns of Cavan and Kells with Dublin, will run through farmland within sight of Ardbraccan’s ancient monastic site' - she turned down the sound. It was already nearly February and she had plenty else to think about. Her class would make their Communion soon and parents had demanded free tea and biscuits for their next Oíche Eolas, scheduled for St. Ultan’s on the 31st. Apparently catering was Muinteoir’s job, alongside educating their children and freezing herself for two hours a month in a strangely shaped church - for free. After a lengthy phone call, the nervous new priest agreed to provide two tankards of tea, while Muinteoir would bring in the milk. If his mass was bad, nothing compared to that long conversation with Father Hyssop about Avonmore milk’s superiority over Tesco’s Own Brand.

For all her trouble, she was adored by the children. Great healer immaculate, she cleaned scrapes and acknowledged big bruises, ‘Yes that is a very big bruise Daithí, but you needn’t punch yourself to keep it black and blue’. Possessor of great sacred knowledge, Muinteoir answered all questions. ‘Muinteoir, what’s the Irish for Jaffa Cake?’, ‘Muinteoir can fish sing songs or just hum tunes?’, ‘Muinteoir, Muinteoir, Muinteoir! An bhfuil céad agam cáca Jaffa le do thoil?’ What she didn’t know, Google promptly told her. So when the 31st came around, she fulfilled her annual tradition and once again watched the instructional video, ‘How to make a Bridget’s Day Cross (Irish Mythology Explained)'. Prepared for tomorrow’s class, she packed up her things to go home.

Engine on. Heater on. Radio, turned up nice and loud. ‘It’s not just the Hill of Tara that matters. It is but the central focus of a wider and deeply significant cultural landscape’. She tuned it all out, thinking only of getting home quick and enjoying her three private hours between school and St. Ultan’s. Her old dog Phelim greeted her as she came in the front door. A springer spaniel/labrador, Phelim was a muscle-bound bullet for most of his life. Impossible to walk because of his strength, they’d simply let him run loose out at Tara to terrorise children, petrify sheep, and piss on the famed Stone of Destiny.

He was older now, although not any bit wiser. She thought he might’ve been clipped on the head by a car, and though the vet said he was fine, he seemed a bit absent. A happy dog, but the kind that barks at his farts. Gentler, now he was almost fourteen, he couldn’t be all that strong anymore. She took out the leash and stuck it onto his collar. Minimal resistance, she’d risk it.

‘Ballachmore Bog - Dogs must be kept on lead - Wildlife Reserve, No Shooting Please’. Ten minutes down the road and she’d never been out to the bog. She strolled in quite careful, testing the waters with her thoughtless old dog who seemed quite happy to stroll. Passing by others just finished their walk, she noticed the knee-high dirt on their clothes. ‘Better be careful not to get mucky, might not get home in time for a bath’. Phelim stared on with his simpleton smile and they walked on together, into the bog.

‘How’s she cuttin’?’, a small chorus met her at every new corner as workmen wheeled out barrows of stone and joggers jiggled on past her. Dogs scrambled on slanted legs to get a sniff at Phelim, as he snapped at orangey-yellow butterflies with stained-glass window wings. ‘The Marsh Fritillary’, she read on a sign, ‘native to this bog, is the only protected butterfly species in Ireland - please leave them be!’ She loved the smell of the bog, like smoke, stout, and her mother burning her bones before bed by the Aga.

Ten minutes since passing the last JCB and the chorus had faded away. ‘It must nearly be time to go home’, and they wandered until the ground, though still marshy, was bogland no more. The landscape familiar and the sky still the same, she felt suddenly lost in a lonely, strange place. Surrounded by endless fields of grey-green, the night fell quick on the land all around her. She walked until Phelim stopped in his tracks. His first real resistance to the lead, it slipped from her wrist and the dog ran away, bounding into a field. Seeing small figures, pale in the evening, she was afraid the old dog saw a lamb. So she ran and she ran and she tripped and she stumbled and she fell into thick, squelching dirt.

Her phone told the time and little else helpful, coverage is no good in that kind of place. A half hour left until meeting the parents, she sat in the muck with her head in her hands. Machine-gun lungs began thumping the air right beside her. All drenched in water, Phelim’s smile was stretched tight against his dim-witted face. He accepted one rub of relief before taking off again at a pace she could follow. The lead lying useless around her left hand.

They stopped at a well, a small hole in the ground surrounded by heavy, black boulders. Freshly bloomed coltsfoot grew just out of the water, while a stream fed the oak, yew and beeches around them. While Phelim drank, she sat tracing the markings on a boulder beside her.

‘Brigid’s knee-prints, or that’s what they’ve told me, left there as she drank from the well. I hope you’re not here trying to bless it, y’know, it doesn’t belong to the Church’. She stared up at the long, grey-haired woman wearing a Leonard Cohen t-shirt and filthy, black wellies. ‘This is the daughter of Dagda’s, Brigid the Goddess, you should know there’s no church-folk allowed! And I’d appreciate you removing your dog from her well, there’s great healing and knowledge that flows through that water’.

This was clearly one of those odd, hippy women who smoked marijuana, didn’t wear bras, and watched TnaG. ‘I’m sorry’, she said and pulled Phelim away, now apparently infused with great celtic wisdom. She felt stupid explaining how she’d been lost ten minutes away from her home but the woman’s face quickly softened.

‘I’m sorry for snapping, I get little peace from the new priest above. Looking for a miracle to distract from that business. But of course, I hadn’t realised there was a stray sod there myself, you can blame those feckers for that now as well!’ The woman shouted as if there were spies in the trees. ‘An foidín mearaí’, she explained, clocking the teacher’s uncertain expression , ‘the sod that sent you out all confused. Denied the burial of their unbaptised children, those poor grieving mothers must’ve gone out to the bog. Walking over those graves can send you down a very bad path’, she leaned over Phelim and gave him a tussle, ‘you’re lucky you had himself there to protect you’.

She didn’t think much of the woman’s weird rambling, but she grinned at the idea of Phelim, Knight Errant. Was eating your vomit part of the chivalric code? She wasn’t so sure.

A small cottage, left by her aunt, the woman invited them in. There was a clock, a table, and some kind of sculpture all glossed with the same varnish and made of dark wood. ‘Pieces I’ve pulled from the bog and restored, there’s more to be gotten from the earth than just fuel’. A bit over-dramatic, but she couldn’t resist this strange woman’s charm. From the rafters was hanging a large Brigid’s Cross and noticing her confusion at this straw-crucifixion, the old woman explained, ‘There’s plenty of things we’ve mixed in with religion, but for me the cross means something else. It’s a connection with the women who made them before me. It’s important, I think, to have something’. The Muinteoir agreed and recalled her mother spreading reed in front of their house to protect them from fire and storms.

They traded similar stories of Biddy Boys and Brídeoga as she remembered old touches she’d long since forgotten. ‘Whether Christian or not’, the old woman concluded, ‘it’s more part of ourselves than of them. You won’t catch them doing this craic out in Rome’. She drove her out to St. Ultan’s with half a litre of milk about ten minutes before the meeting should end. It seemed that some of the parents, with the pandering priest’s full blessing, were intoxicated by the good grace of God. Father Kearney’s spirit cupboard had long been discussed but under the new fawning Father all mysteries were revealed. Embedded at last, Father Hyssop hiccupped as he held the kind woman’s arm and sneered, ‘So you’re the aul bitch that’s been hoarding our well’.

The kids, having learned about the Salmon last year, were fascinated by Phelim’s new, magical knowledge and crowded the dog who stared into space, vacant as ever. Even as Phelim relieved himself against Our Lady Immaculate, young Daithí solemnly whispered ‘uisce coisreacain’ and blessed himself. When Muinteoir sat down with her husband at home, she swore she was mortified, but she smiled as she said it and the dog got two dinners.

‘While sitting by the deathbed of a dying Pagan Chieftain, Saint Brigid weaved a cross out of rushes, and told him the word of the Lord. Before he died, the Chieftain was Christian’. She x’d out of the tab and closed her computer. As she stared at her class of small children, each one smiling with a cross in their hands, she decided to tell them a different story entirely. It was about her own childhood, making circular crosses for mothers in labour, three-pronged crosses for cattle and sheep, and four-pronged crosses to welcome the Spring. She never spoke a single word of the Lord.

After big break, she handed out sheets,

Líon na Bearnaí

Is saoire ______ é Feabhra 1, ag ceiliúradh ______. ________ a thugtar air.

(February 1st is a ______ holiday, celebrating the life of _______. It is known as ________)